Packer at War

Since the Civil War, the staff and students of The Packer Collegiate Institute have been intermittently called upon to meet the challenges posed by a nation at war.

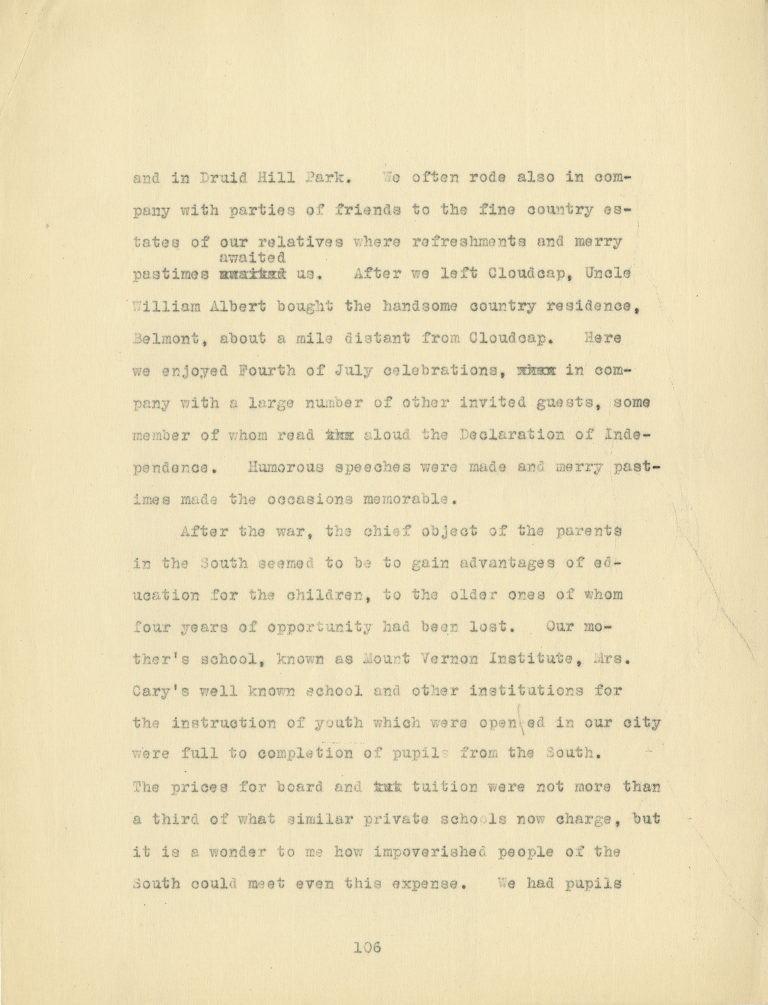

The American Civil War

Packer’s student body reflected the sectional divisions of the Civil War. Among the Packer student body were twelve students from the Southern United States. While these students wore palmetto badges to express their solidarity with the South, the other students wore badges of red, white, and blue. Eventually, these political expressions caused enough friction that the school’s principal, Dr. Alonzo Crittenden, reportedly forbade the wearing of any badges.

When the war began, most Packer students experienced it through their exposure to soldier parades, recruitment drives, and arriving hospital trains. The response of Packer students, like most women of the time, consisted of contributing to the war effort by knitting items of clothing and raising money. In 1864, Packer staff and students raised thousands of dollars by participating in the Sanitary Fair held at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, then located on Montague Street. In addition, the senior class of Packer raised an additional $941.88 by providing entertainment at the event.

With the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, Packer students and faculty mirrored the grief of many Brooklynites and Americans. At the news of Lincoln’s death, students were dismissed from classes and the school remained closed until the end of Lincoln’s public funeral.

World War I

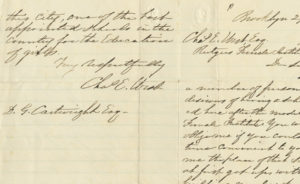

In addition to knitting and raising money for relief organizations like the Red Cross, during World War I every effort was made to keep Packer students informed of world events. Packer faculty members gave special lectures on topics ranging from the origins of the Russian Revolution to Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points plan.

While for the most part, Packer staff and students united to support the war effort, the school was not immune to the wave of anti-German sentiment that spread across the United States during the war years. For example, Packer’s German language department had employed four teachers in 1914, but by 1919 it had been cut to a staff of one.

World War II

The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 brought the United States into World War II. Packer had one student of Japanese descent enrolled at the time. In contrast to incidences of anti-German sentiment at Packer during World War I, this student was respected and treated no differently than she had been prior to the war.

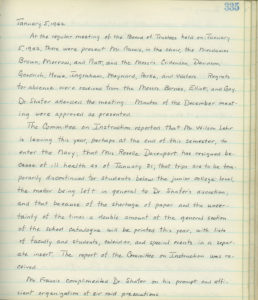

All at Packer felt shortages in food and equipment, including such basics as paper, during the war. Some faculty members left Packer to join the war effort. These included drama teacher Wilson Lehr, who joined the Navy in 1942, and Isabel Blair of the Latin department, who joined the United States Women’s Naval Reserve.

Fears of invasion and attacks on the home front were also real concerns and prompted all citizens to prepare accordingly. In response, Packer installed an alarm system, fingerprinted and issued identity bracelets to all students, made evacuation plans, and practiced emergency drills.

By the end of the war in 1945, Packer, like the rest of the United States, was ready to move on to better times. However, Packer students continued to remember Europe’s neediest.

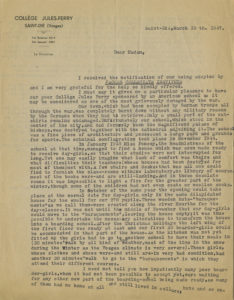

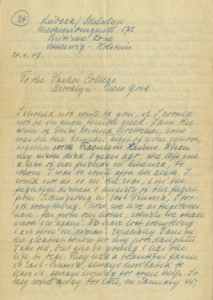

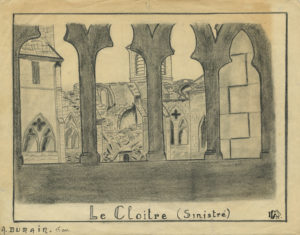

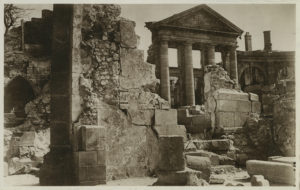

In 1946, the faculty and students of Packer took on the sponsorship of a French school devastated by war. Collège Jules Ferry was an all-girls school located in Saint Dié-des-Vosges, a French town that had been occupied then destroyed by the Germans in November 1944.

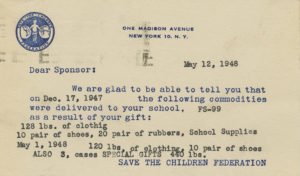

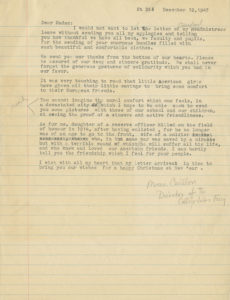

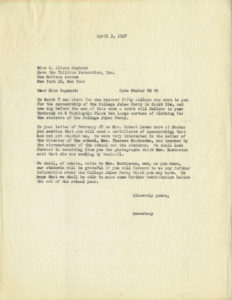

The relationship between Collège Jules Ferry and Packer afforded Packer students the opportunity to help, but also to learn about the experiences of girls like themselves who lived overseas and had experienced the war firsthand. The partnership, which had been organized by the Save the Children Federation, included letter exchanges, as well as donations of money, clothing, and other essential items. In this way, the sponsorship became more than just a one-way exchange of goods. As Madame Thérèse Montredon, the director of Jules Ferry wrote, “I sincerely believe that the adoption of a French school by an American one will help the general understanding between our two nations and all my efforts will always be directed towards that aim.”

Related documents

The Packer Collegiate Institute Board of Trustees meeting minutes, 1942/01/05

Packer and the War pamphlet, 1942

Packer Current Items, Vol. XXXV, No. 2, 1944

Postcard sent from Save the Children Federation to The Packer Collegiate Institute, 1948/05/12

Letter from Theresa Montredon to Packer Collegiate Institute, 1947/03/10

Letters from the assistant headmistress of College Jules-Ferry (Saint-Die-des-Vosges, France) to The Packer Collegiate Institute, 1947

Correspondence between The Packer Collegiate Institute and Save the Children Federation, 1947-1948

Letter from Alice Perkuhn to The Packer Collegiate Institute, 1947/04/28

Letters from students at College Jules-Ferry (Saint-Die-des-Vosges, France) to The Packer Collegiate Institute, 1948

[Woman and young girl inside a home], 1947 ca.

Le Cloitre (Sinistré), 1947 ca.

[Entrance to Jules Ferry], 1948 ca.

[Entrance to Jules Ferry], 1948 ca.