A Curriculum for the Times

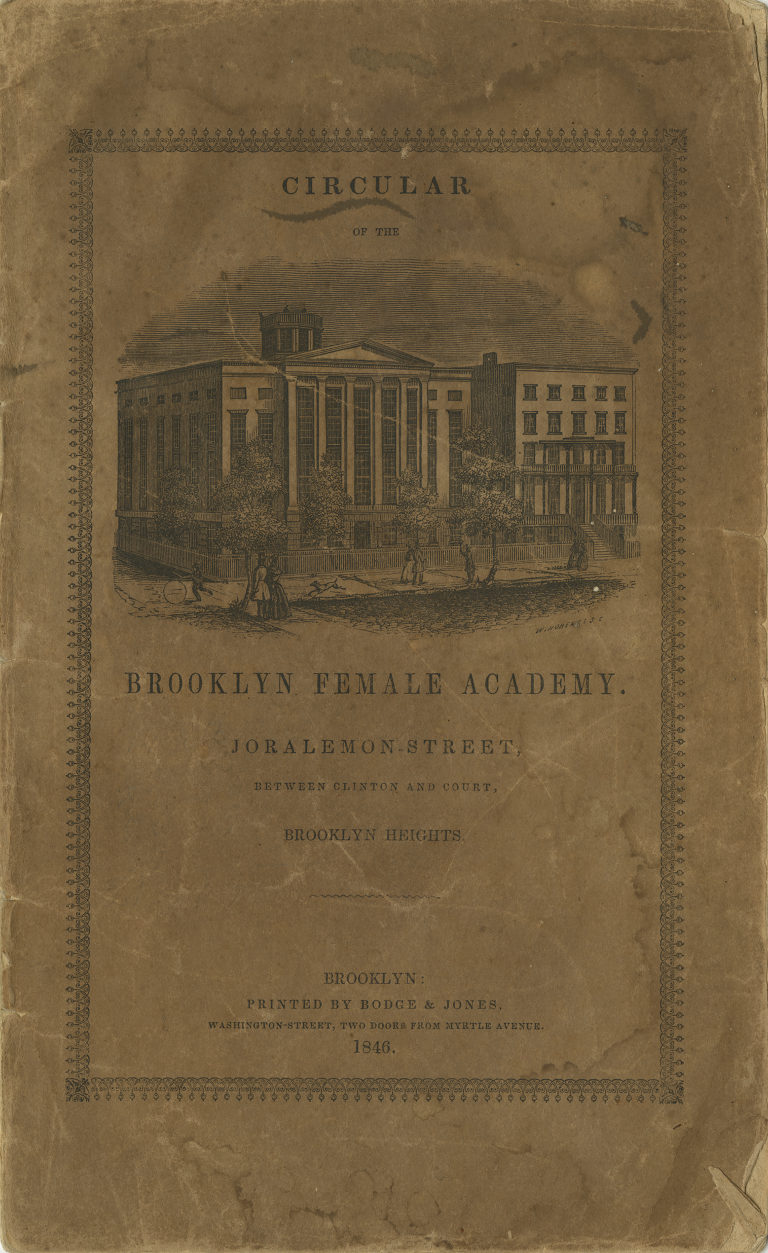

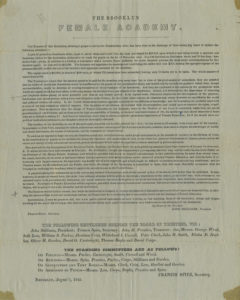

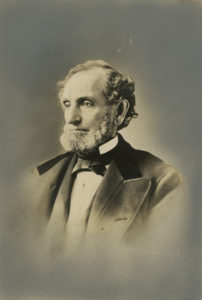

Brooklyn Female Academy’s (BFA) first president, Dr. Alonzo Crittenden, was largely responsible for shaping the school’s early curriculum. Crittenden, who had formerly been the principal of the Albany Female Academy, eschewed rote memorization in favor of teaching methods that incorporated reasoning and creative thought. The primary goal of the new school was identified in its first circular from 1846, which read:

The Trustees of the Brooklyn Female Academy, in presenting their first circular, deem it proper to state, that they have endeavored to found a Seminary, which will afford to young ladies the same facilities for acquiring a good English and Classical education, that are provided for young men at the best collegiate institutions in the country.

When BFA opened, it was organized into three departments of education:

- Primary: It offered students younger than eight years old courses in spelling, math, and geography.

- Academic: It offered students ages eight to fourteen years old the same courses as the primary level, but also more advanced courses in topics such as science, Latin, and rhetoric.

- Collegiate: It offered students older than fourteen years old a variety of courses, including physics, botany, philosophy, constitutional law, and bookkeeping.

Studies in foreign languages and the arts were also offered in each department and included courses in vocal music, drawing, and needlework. Finally, religious education was an integral part of the BFA and The Packer Collegiate Institute curriculum. Young students took courses in the New Testament and the geography of the Bible, while older students explored the philosophy of natural theology, which used both the evidence science and history provided to prove God’s existence.

While the goals of BFA may have been progressive for their time, they were far from revolutionary. BFA’s leaders did not seek to challenge the idea that an upper-class woman’s place was ultimately in the home. Yet despite this, many of its alumni—including famed suffragist Lucy Burns—did go on to use the skills they learned at BFA and Packer to challenge the status quo and to advance the role of women in society.

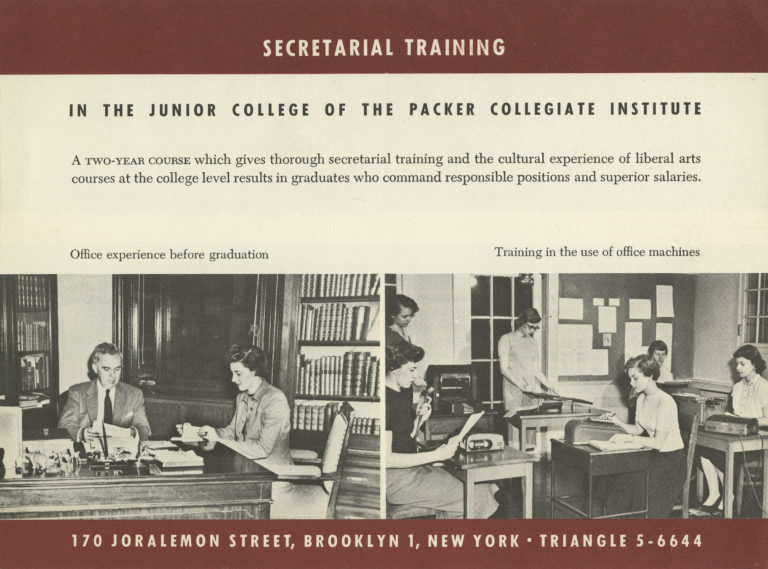

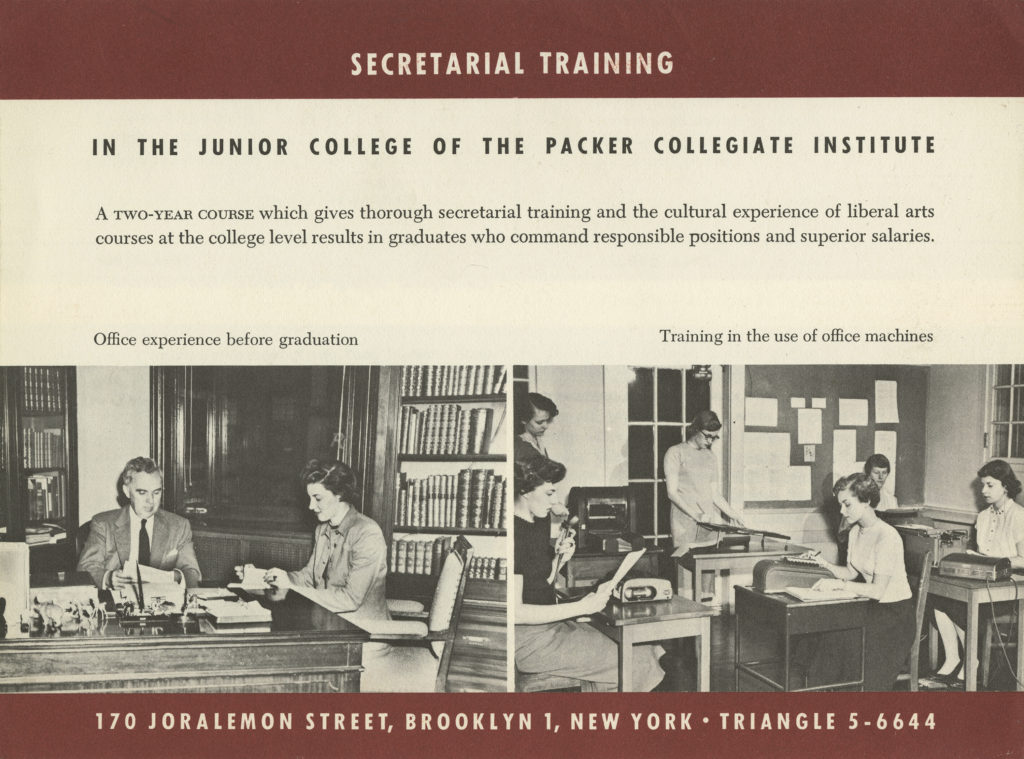

As the needs of society and its students changed, so did the curriculum of Packer. In the 1940s, the school opened a secretarial department as part of its junior college. This program provided essential skills to the growing number of women entering the workforce. As noted in a course pamphlet, the two-year course was “designed to train students to become secretaries with the desirable stenographic skills, to speak and write well, to have poise and good judgment, to understand business and the business world, and to hold proper attitudes toward work, leisure, and citizenship.”

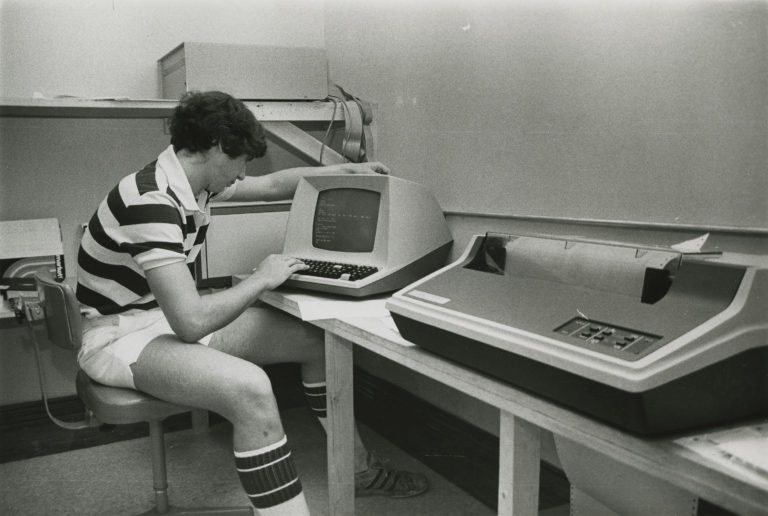

As the years have passed, Packer curricula have continued to evolve to meet the educational needs of its students and to prepare them for their futures. Significant changes have included the change to coeducational instruction and the introduction of computer studies.